We have recently been tasked with improving the search function of a large corporation's self-help website. We love tasks like this – as basic as they may seem at first glance – because they allow us to re-examine something that we take for granted; something where we believe that we "just need to follow the best practice". As designers, it is helpful to look out for paradigm shifts that challenge our core assumptions.

For search, this is especially relevant, as we humans have been dealing with this since we started to gather more information than we could hold readily at the forefront of our minds – which is to say: It's a problem that we've had since the early post-ape days.

Re-examine the basics: How search has changed

As we added new fundamental ways of communicating to our arsenal – from the first spoken and later first written words carved into stone, to mass printing, all the way up to our digital age of limitless text distribution and text generation – we have changed how we search and what we want to know time and time again.

Imagine an early knowledge worker of sorts: a twelfth-century monk. Retrieving information for him was totally different than it was for people during the Victorian Age, and especially different than it is for us today. While we have outsourced large capacities of our memory to computers and rely on search features with complicated algorithms to fetch the relevant information for us, the monk had mainly one place to search: His mind.

Sure, monasteries were famously the intellectual hubs of the Middle Ages and home to many libraries, but, as Ivan Illich describes in his book "In the Vineyard of the Text", key innovations that would make it easier to search for and retrieve knowledge from books were not yet made. Page numbers, chapter headers, and indexes all had to be invented first. And only the printing press made it feasible to have a high enough volume of books, essays and pamphlets that you could sensibly compare texts to each other.

So search has been for a very long time a mental technique first and foremost; a way to access your mind's own library and recite what you have heard (heard is indeed the correct term here even when talking about written text, as books were thought of as "recordings" of speech – very much rooted in a world where the spoken word dominated as a medium).

It is fair, though, to characterize us, humans, as information hungry, regardless of the age we are born or the medium that dominates how we convey information. Psychologist George Miller famously called our species "informavores" for a reason!

But how we look for this information has shifted, as the example above hopefully illustrates a bit. And we think it is changing again today, which makes a re-examination and challenge of the basics all the more important.

The status quo of search

So, how do you look for information today? You just google it, right? The prominent search bar, prompting us to input any query, and the list of links that it outputs as a result have been a fundamental staple of the web for a long time.

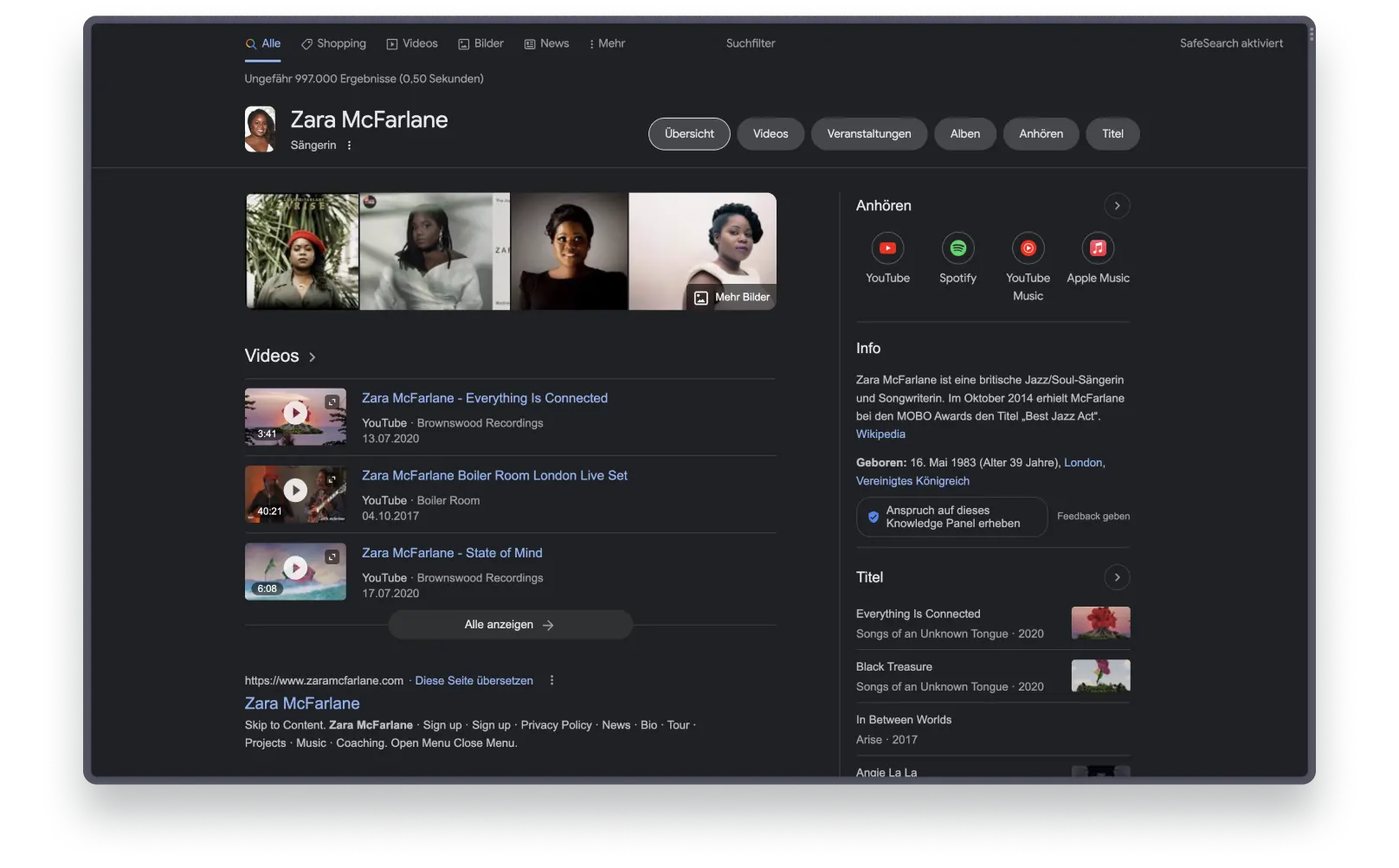

A lot of research has gone into this experience. From psychological research we know, for example, that it is best to present information in different "cognitive styles". Some users prefer visual information, while others focus on text; some people need their information structured, while others are OK with a more fuzzy presentation (see Information seeking on the web: Effects of user and task variables and Cognitive styles in the context of modern psychology: toward an integrated framework of cognitive style for more details). That's why you will see not only the famous "ten blue links" on Google results these days but also a lot of images and videos and a box with structured, key information on the right-hand side.

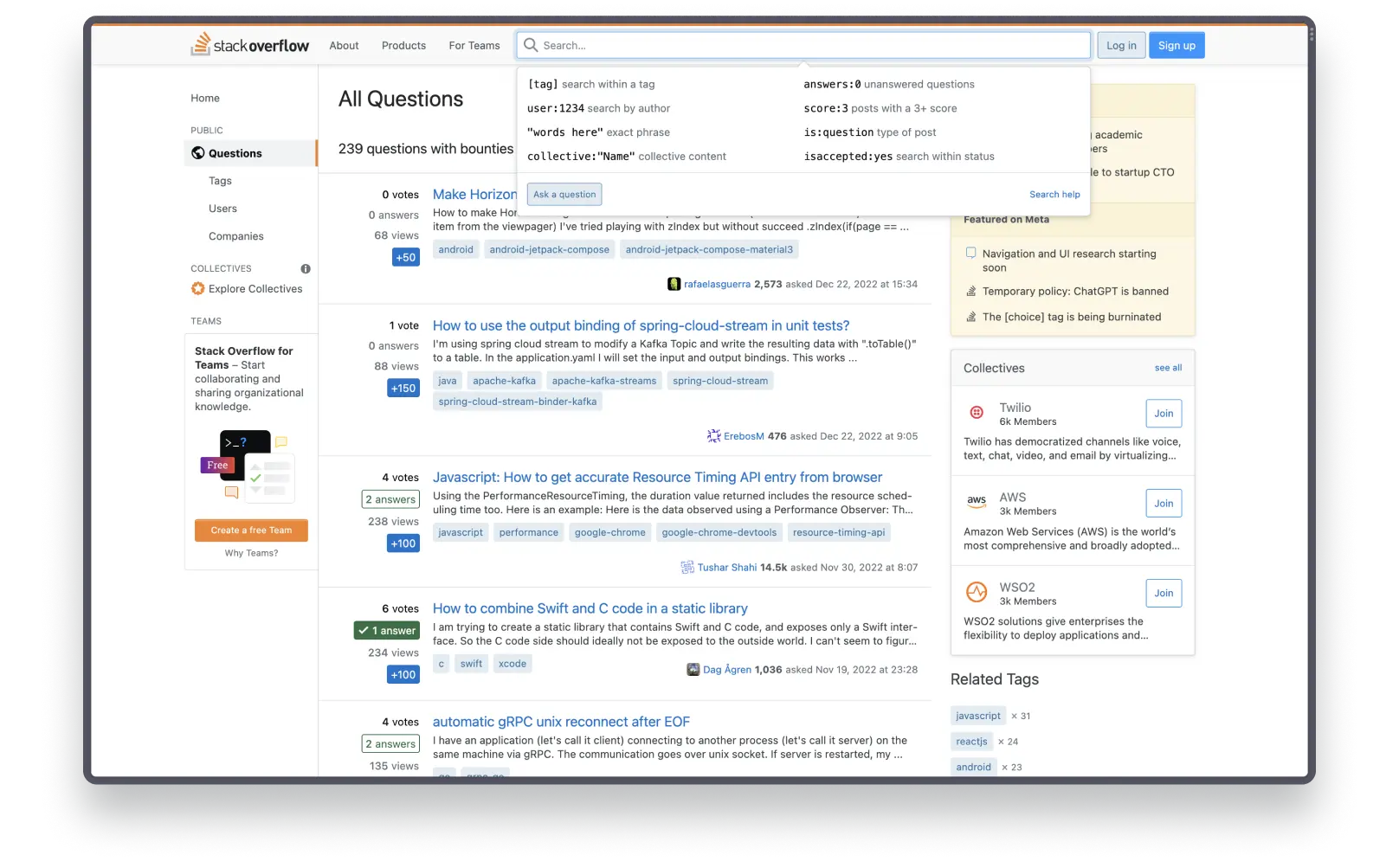

We also know that we have to take into account the user's expertise. Some users are technical savvy and can deal with search operators, no problem. Others may not be technical experts but know a lot about the subject that they are investigating. The search experience should make it easy to excel in both dimensions: Technical understanding of how search works, and mastering a subject matter (see Orienteering in an Information Landscape: How Information Seekers Get From Here to There). That's why you will see hints of how to use special search operators when clicking in the search bar on Stack Overflow for example. They increase the Learnability of the system, allowing everyone to become a technical search expert.

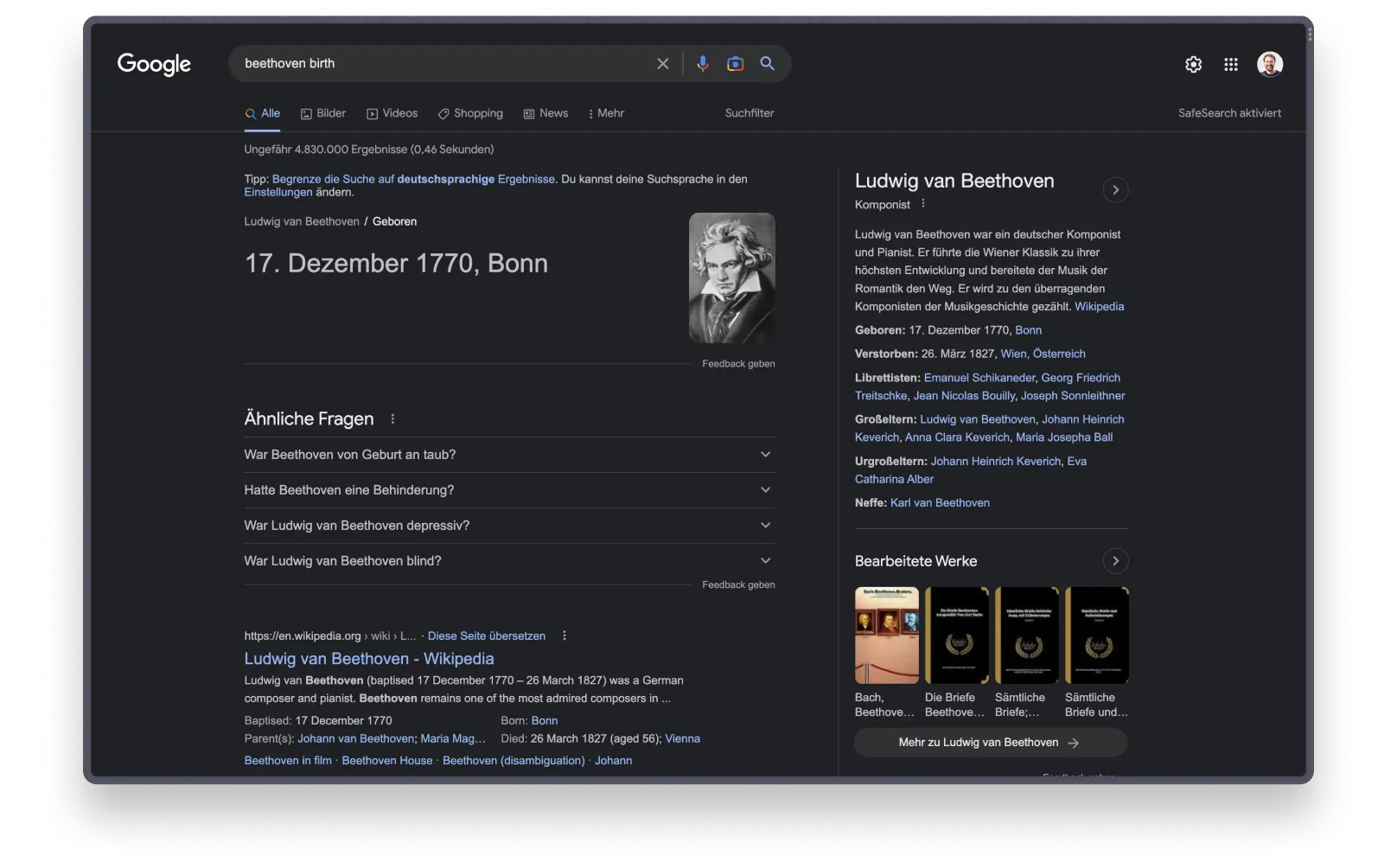

We also understand that there are different motivations to why we search and that we need to account for this in the search experience. It might be that a user simply wants to look up information and retrieve a result. Taking Google as an example again, they take this into account and show a result immediately for fact retrieval queries.

Other times we search because we want to learn something new and dive deeper into a specific topic. Showing a simple fact is not enough here - rather it is about structuring the results in a way that gives various important entry points to the subject. Looking at the picture above makes this clear: If we wanted to know even more about Beethoven we would have a plethora of entry points: A summary, key dates of his life, his family, works about him, related questions from other users, and of course the list of most highly ranked entries for this topic. A treasure trove for someone exploring a topic (see Designing the Search Experience for more on the "Lookup, Learn, Investigate" intents of search).

Figuring out the motivation is not trivial, but we are also getting better at this. Through machine learning we are now able to distinguish between different intents - e.g. if you are looking for an offer to buy a certain movie, we can immediately show results from shops around the web.

If reading all of this leaves the impression that we have search in digital products all figured out, well, we'd say yes and no. We think we have good practices and research for how search works now, but, as alluded to in the introduction, we think we are at the edge of the next big shift.

Search of the future

In another article, we discussed how AI agents could support a designer's work at the various stages of the process. One idea we came up with was that during the research phase we could instruct the program to go out to search, collect and summarize all the relevant information regarding the core problem of the project.

For the user, search becomes more of a question of providing a good briefing. For us designers, though, it becomes a challenge of making sure that the AI gets all the info necessary to successfully fulfill its task and figure out how to best present the results (maybe a "president's morning briefing" might be a good format to start with?).

The next question is how we would deal with an AI agent that provides search results proactively and predicatively – meaning, before we have even formulated what is interesting to us. Based on the history of our behavior and our interests, the mails and messages we get from work, and the conversations we have, it could be feasible to have the AI prepare results before you even know that you need them. Navigating the privacy challenges and user agency problems around this will be a big task, but one that I'm sure we will deal with sooner rather than later.

It is best to be prepared for the next shift, and challenge what we seem to know.